AI. Artificial intelligence. Neural networks. Large language models. Agents. Buzzwords tossed around like casual white supremacy at a tech party. We're living in the Age of the Algorithm, grinning like fools as we watch the machines learn to mimic us; poorly, beautifully, eerily. It's thrilling, sure. A real fireworks show of possibility. But let's not kid ourselves. We're drifting into uncharted waters with no map, no compass. Just a cocktail of hype and hubris sloshing around in our collective belly.

Uncertainty is necessary fuel. The jolt that kicks change into gear. I believe in change like I believe in oxygen. But the question hanging in the air like stale cigar smoke is this: is AI actually a revolution in design, or just a slick new mask over the same old capitalist con? A polished veneer slapped over centuries of creative labor being mined, packaged, and exploited without a second thought. The tools got smarter, but is the game still rigged?

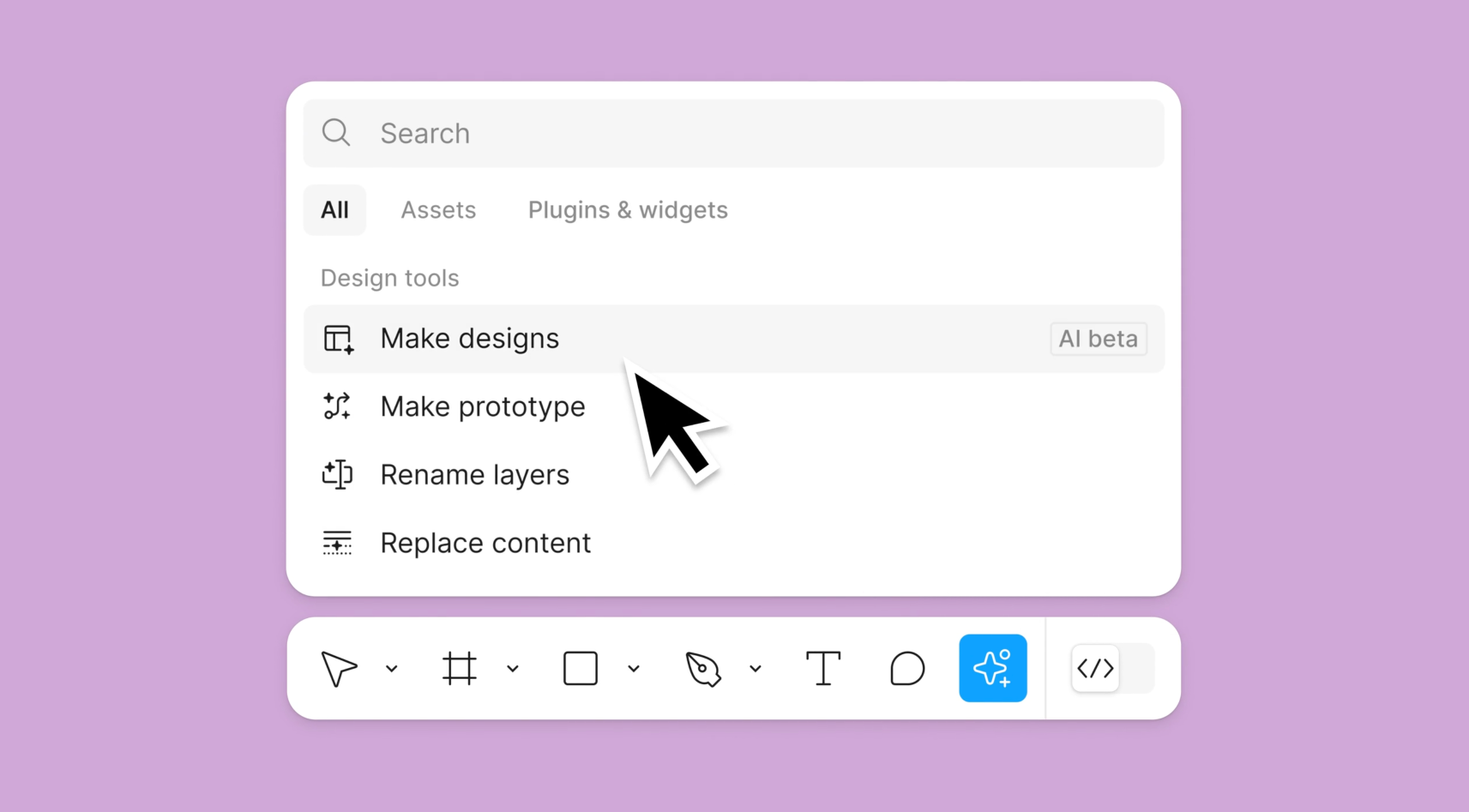

Figma dropped a new shiny little bomb last week; a handful of AI-fueled features, all wrapped in sleek marketing and breathless optimism. One in particular, Make Designs, lit a fire under the design community's collective ass. Not the good kind. We're talking full-blown existential dread; wide-eyed, mouth-foaming, bloodshot panic.

The premise is simple. Instead of drawing interface designs ourselves, Figma wants us to let AI do it. At face value, this sounds exciting. After all, who likes pushing pixels around until their brain melts? Haven't we spent years—decades, even—fighting the idiotic notion that pushing pixels is all we do? That our value is tied to the tools and not the thinking?

For a lot of folks, the real gut-punch here isn't just that Figma, the holy grail of modern product design, is playing footsie with automation. It's that it's testing the waters on cutting designers out of the entire equation. Imagine being a business owner watching AI spit out a decent-enough interface in seconds. Why pay a human? That creeping thought, that quiet little apocalypse, is what's keeping designers up at night. This isn't just a shiny new feature. It's a signal flare. Another step in the long, bleak march toward oblivion by tech tools that promise efficiency but deliver burnout, higher quotas, tighter deadlines, more pressure, and less pay for the survivors. The same old song, now with an artificial backing track and zero attribution to the original artist.

Sure, Make Designs could be a godsend. An antidote to the mind-numbing ritual of churning out mockups like some wireframing automaton. But it also has the potential to cure designers of their careers entirely. Not because the tool itself is evil. No, it's just code doing what it's told. But because of the inevitable knee-jerk reaction from the folks holding the purse strings. The ones who already see design as a line item to be slashed in pursuit of that sweet, sweet shareholder value. To them, AI doesn't streamline the job, it eliminates the need for the job altogether. And in a world obsessed with efficiency, that's a horrifying prospect. We're not automating tasks anymore; we're automating people.

But I'm not about to spiral into another elegy for lost jobs and vaporized paychecks. That story writes itself, and it's already halfway through the news cycle. What follows instead are clear-eyed (and maybe a little blistered) meditations on how this shiny new AI feature might mangle product quality, especially for the people who always get left out of the conversation. The folks on the margins. The ones algorithms tend to forget. By the time we're done, you'll see exactly why I think AI's not ready to replace designers. Not just because it fumbles the craft, but because it doesn't yet grasp what accessibility means. Not really. Not in any way that matters.

Everyone's Responsibility Top

AI's output, as of the time of this writing, is a direct reflection of its training. It knows only what it's fed, and what it's fed is data scraped from the bowels of the internet and the backs of countless unpaid creatives. It can't empathize. It can't rationalize. Like an infant, it just regurgitates what it eats.

Of course, an argument can be made—heck, should be made—that this isn't just an AI problem. Human designers aren't exactly divine wells of original thought either. We're all stitched together from scraps of our environment, our education, our culture, our biases; conscious and otherwise. We're walking neural networks with baggage. Sponges soaked in everything we've ever seen, touched, loved, feared. "There's nothing new under the sun," the old line goes, and it's true. Most of what we create is remix, reinterpretation, homage with new border radii.

But, we can empathize and rationalize, and we often redefine that which informs our work, through our work. We can sit in a room with someone who moves through the world differently and feel the gaps in our understanding. We can confront our blind spots, reckon with them, and make choices rooted in empathy, not just pattern recognition. This empathy is how we improve experiences for the quiet, the overlooked, the inconvenient; how we break the mold to include the underrepresented and the marginalized. As designers, we're each responsible for making things that work for everyone, not just the people things have worked for in the past. In our field, edge cases may not be prioritized, but they should also never be ignored.

So yeah, we're both flawed; humans and machines. But only one of us can change the output and the intention behind it. Only one of us can look at a design and say, “This might work for me, but who is it failing?” And that, right there, is the soul of the thing. The ghost that the machine still doesn't have.

AI lags here because the people building these networks aren't typically the ones navigating the world with a screen reader, or trying to tap a tiny button with limited motor control, or translating meaning through layers of cognitive load. The data is biased. It's incomplete. It's riddled with assumptions baked into decades of “average user” thinking. That's not just a flaw, it's the design. Garbage in, garbage everywhere.

AI can't understand what it means to build for someone with low vision trying to use a government site on a three-year-old Android phone with a cracked screen. It doesn't stop to consider whether a form flow actually makes sense to someone dealing with dyslexia or short-term memory loss. It has no lived experience. No context. No empathy. And without designers, real designers, asking the hard questions and pushing back on the defaults, what we'll get isn't inclusive. It's a polished simulation of inclusion. A veneer.

And when AI gets it wrong, it doesn't know it got it wrong. It doesn't feel the weight of that failure. It doesn't sit with the user who couldn't check out because the form didn't play nice with a screen reader. It just moves on and spits out the next thing.

Accessibility isn't a checklist. It's not a plugin. It's not a bullet point in a product brief. It's a mindset. A muscle. A moral stance. And you can't train that into a model. Not unless the people who live it and fight for it have their hands on the wheel.

So here we are. AI, the so-called disruptor of the status quo, the great emancipator of labor, the high priest of innovation. But it isn't breaking the system. It's reinforcing it. At scale. With a smile.

Because when your data diet is the existing web—the same web built on exclusion, ignorance, and one-size-fits-most thinking—what else can you expect but a future that looks suspiciously like the past?

Here's the blunt facts. About 13% of people alive today live with some form of disability. That's one in eight humans. And yet, according to UserWay, only 3% of websites are accessible to them. Three. Percent. That's not a bug in the system. That is the system.

Now take that system. Feed it into a large language model. Bake it in. Train it. Normalize it. Call it progress.

What kind of outcome should we expect from that?

You can't create inclusive solutions from exclusive data. You can't synthesize equity from a source that's riddled with bias. And yet we expect these models, built on a foundation of neglect, to suddenly give us designs that work for everyone? That's not optimism. That's delusion with a startup pitch deck. Insanity as a business model.

Until we fix the source; until we reimagine the raw material of the internet with everyone in mind, we are just accelerating injustice. Automating the same tired exclusions. Reinforcing the same blind spots that human designers have fought for decades to expose and dismantle. And we're taking the soldiers out of the fight.

If the web itself only includes a privileged sliver of the human experience, then that's exactly what AI will learn. And repeat. And amplify.

Thus, the likely outcome of tools like Figma's Make Designs isn't some utopian leap in productivity or a democratization of creativity. It's a slow, staggering collapse in design quality, felt most acutely by the very people who can least afford it.

The groups hit hardest will be the same ones always left on the fringes. People with disabilities. Neurodivergent folks. Users navigating products in their second, third, or fourth language. Older adults. Low-bandwidth users. Anyone whose lived experience doesn't neatly fit into the default templates of mainstream culture.

These are the people who rely on accessible, inclusive design not as a nice-to-have, but as a requirement for participation. And they're the ones most likely to be failed when the design process is reduced to a prompt and a prediction.

When inclusivity becomes collateral damage in the pursuit of efficiency, what we're left with is not innovation, it's erasure.

Because if you train a mirror on a broken world, all it can do is reflect the cracks.

Poorly Performing Prompt Products Top

People in some management roles are already halfway to becoming prompt engineers. A lot of their job is wrangling requirements and nodding at PowerPoints anyway. Just toss a large language model into the mix and suddenly they're digital sorcerers, spitting out shiny prototypes at the speed of thought. It's a beautiful scam. The cost of designing things nosedives, shareholders wet themselves with joy, and the whole process starts to smell like fast food; cheap, immediate, and suspiciously uniform. Welcome to the algorithmic arms race, a race to the bottom where the soul of your product is sold for a handful of tokens and a quarterly earnings bump.

As designers vanish into the algorithmic ether, so too does any real fight for accessibility; the messy, human kind that doesn't fit cleanly into a requirements doc. What's left behind is a graveyard of best practices, rotting like roadkill under the hot sun of outdated standards. Sure, some prompt engineer might occasionally toss in “make it accessible” as a bullet point, like a garnish on a plate of status quo bolognese. But without fresh ideas; the kind that come from lived experience, sweat, and rebellion; these models will regurgitate the same sanitized sludge. It's digital inbreeding. Homogenized output—endlessly replicated like a virus in an outdoor meat market—optimized for the average user. And what works for the “average” user sure as heck isn't accessible. Ask anyone still standing in the shadows. Algorithms don't care about edge cases. They filter them out like noise. And when the noise is people, well, that's not just a design problem, that's a human one.

Senior designers, who've survived a dozen redesigns and lived to tell the tale, they'll stick around for a bit. In so far as one can these days. Their scars are suddenly valuable again, you see. They know how to navigate the system, how to talk execs off the ledge, and how to cram accessibility into product roadmaps with less breathing room than a plastic bag. Their bargaining power might even go up. Temporarily. But the clock is ticking. They'll cash out, burn out, or quietly disappear into retirement as the tide rolls in.

It's the fresh blood that gets slaughtered. Junior designers, bright-eyed grads with crisp portfolios and $100k grad school debt. They're walking into a buzzsaw. Why waste time training up fresh designers when your Product Manager can just throw a few buzzwords into a prompt and get passable output before lunch? Why even have anyone else at all do it when your CEO can play pretend and generate mockups on their own, without all the messy friction of someone else questioning their half-baked ideas? No pushback, no critique, no inconvenient conversations about “users” or “ethics.” Just them, their prompt, and the cold comfort of machine-generated affirmation.

The result of all this is a talent wasteland, overrun by amateurs calling themselves designers, whose only skill is typing prompts into boxes. We'll all suffer the consequences of a world full of prompt products, but the marginalized will feel it the most. Where accessibility is not just an afterthought, but no longer exists at all.

The Light At The End Top

But hey, it's not all doom and dystopia. There's a bright side hiding under the ash heap, and it's also powered by prompts. Large language models aren't just harbingers of enshittification, they're also damn good assistants when pointed in the right direction. Automating the junk that designers hate? Beautiful. Necessary, even. Get a load of these prompts:

- “Using Figma best practice, optimize this component to include the least number of variants and layers possible...” Boom. Less bloat, more brainspace.

- “Translate these bulleted user shadowing notes into a user journey diagram...” Hell yes. Visualize the chaos, complete with emotional turbulence mapped out like a weather report.

- “Remove all the unnecessary groups from this frame...” Finally, vengeance against whoever nested 47 frames inside one another.

- “Name all the layers consistently...” Sweet relief from the tyranny of Rectangle 237.

- “Swap out hex codes for tokenized color variables...” Welcome to the age of design systems doing what they promised.

- “Replace junky non-components with polished library pieces...” Now we're cooking with atomic design gas.

- “Create a simple table that explains this component's properties...” Documentation without the tears.

These are the kinds of prompts that don't replace designers, they liberate them. Strip away the grunt work. Let the machines do the menial crap so humans can get back to the weird, emotional, soul-stretching act of solving problems that require lateral thinking. The human in the loop? More like the machine in the loop, while the human runs the show.

The landscape is shifting, and the old ways are crumbling. But buried in the rubble are tools sharp enough to build something better, if we still have the guts to pick them up.

Liberation Or Exploitation: Choose Your Own Adventure Top

The dream, remember, was never to grind ourselves into dust under fluorescent lights and Jira tickets. The idyllic techno-future we were promised, sold in glossy keynote slides and TED talks, was one where machines did the busywork and we got our lives back. More time with our families. With our aging parents, with our children before they become strangers. More time painting, playing, dreaming, living. That was the pitch.

In that vision, the day job—this soul-sucking need to assign all our worth to a singular capitalist-purpose—was meant to fade into obsolescence. Tools like AI could be the crowbar that cracks the chains of wage labor. A liberation engine. But in practice? Right now, it's more like a factory-installed shortcut to exploitation. Today's tools are nowhere near ready to replace human designers, and society isn't even remotely prepared for what happens if they try. Instead of freeing us, we risk using this technology to double down on the oppressive systems that keep people locked out, burned out, and creatively bankrupt.

At the current velocity, we're not heading toward utopia; we're barreling into a future where design is stripped for parts, experience is ignored for speed, and quality is sacrificed at the altar of short-term gain. Junior designers won't get their shot. The concept of user research will be tossed out with the bath water. The people already on the outside will be left in the cold.

But let's be clear. AI isn't the enemy. It's just a tool; sharp, indifferent, and only as good as the hands that wield it. The real fight is a human one. A battle against the broken, perverted incentives of profit-at-any-cost economics.

So here's the call: use the tools. Push them. Break them. Automate the junk, the sludge, the repetitive tedium. But don't forget the messy, difficult, human parts; the empathy, the inclusion, the craft. That's not legacy thinking. That's the soul of the work. And it's worth defending.